The Rich Man and Lazarus

An Exposition of Luke 16:19-31 Showing That It Has Been Misapplied to the Doctrine of Eternal Torment

Note: The following essay is an extended note written as a companion to our work A Challenge to the Doctrine of Eternal Torment. Please see that page for more commentary on other passages which are set forth in order to prove the doctrine of eternal torment.

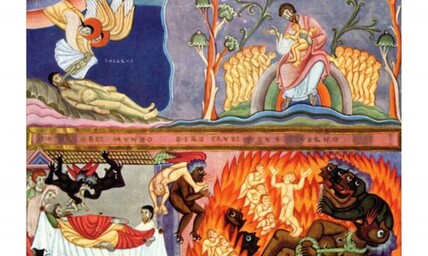

There was a certain rich man, which was clothed in purple and fine linen, and fared sumptuously every day: And there was a certain beggar named Lazarus, which was laid at his gate, full of sores, And desiring to be fed with the crumbs which fell from the rich man’s table: moreover the dogs came and licked his sores. And it came to pass, that the beggar died, and was carried by the angels into Abraham’s bosom: the rich man also died, and was buried; And in hell he lift up his eyes, being in torments, and seeth Abraham afar off, and Lazarus in his bosom. And he cried and said, Father Abraham, have mercy on me, and send Lazarus, that he may dip the tip of his finger in water, and cool my tongue; for I am tormented in this flame. But Abraham said, Son, remember that thou in thy lifetime receivedst thy good things, and likewise Lazarus evil things: but now he is comforted, and thou art tormented. And beside all this, between us and you there is a great gulf fixed: so that they which would pass from hence to you cannot; neither can they pass to us, that would come from thence. Then he said, I pray thee therefore, father, that thou wouldest send him to my father’s house: For I have five brethren; that he may testify unto them, lest they also come into this place of torment. Abraham saith unto him, They have Moses and the prophets; let them hear them. And he said, Nay, father Abraham: but if one went unto them from the dead, they will repent. And he said unto him, If they hear not Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded, though one rose from the dead. (Luke 16:19–31)

I feel obliged to provide some extended comment on the Story of the Rich Man and Lazarus due to the great (and in my view wholly unwarranted) weight given to the passage by the teachers of eternal torment.

That this passage should be given such weight at all is a bit of a mystery to me for one simple reason — Namely, that the “hell” with which this passage has to do is represented by the Greek word hades which the scriptures take great care to distinguish from both the “hell” designated by the Greek word gehenna, and the “lake of fire” of the Book of Revelation. Hades is to be emptied of the dead within it prior to the final judgment of mankind, and it is hades which is to be destroyed in the “lake of fire”. See Revelation 20:11-15.

Therefore, I cannot stress enough that no matter what conclusions we draw from this text, they are simply irrelevant concerning the eternal and final destiny of mankind. Many a sermon about the horrors of hell contain descriptions of the torment of the “Rich Man”. Almost none explain to their hearers that the “hell” of this passage is not, in their view,the supposedly eternal hell warned of elsewhere.

Traditional believers in eternal torment insist that this passage must be taken in its most strictly literal sense. We are told boldly, and with the utmost conviction, that this passage is not a parable. But how do the teachers of eternal torment know that? What proof have they offered that this passage is not a parable? Well, we are told that Jesus never used proper names in parables, and thus because this passage uses the proper name “Lazarus”, therefore it is not a parable.

But I can’t help but feel that this type of reasoning could only be believed by those who advance it to defend their position. Their logic simply begs the question. For if this passage IS a parable, then it is not true that Jesus never used proper names in parables. It also never seems to have occurred to the believers in eternal torment that Jesus may have had a very good reason to use the name “Lazarus” within this particular parable.

But beyond this, there is solid evidence that the passage is indeed a parable. Notice: Just who was Jesus addressing when he told the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus?

That this passage should be given such weight at all is a bit of a mystery to me for one simple reason — Namely, that the “hell” with which this passage has to do is represented by the Greek word hades which the scriptures take great care to distinguish from both the “hell” designated by the Greek word gehenna, and the “lake of fire” of the Book of Revelation. Hades is to be emptied of the dead within it prior to the final judgment of mankind, and it is hades which is to be destroyed in the “lake of fire”. See Revelation 20:11-15.

Therefore, I cannot stress enough that no matter what conclusions we draw from this text, they are simply irrelevant concerning the eternal and final destiny of mankind. Many a sermon about the horrors of hell contain descriptions of the torment of the “Rich Man”. Almost none explain to their hearers that the “hell” of this passage is not, in their view,the supposedly eternal hell warned of elsewhere.

Traditional believers in eternal torment insist that this passage must be taken in its most strictly literal sense. We are told boldly, and with the utmost conviction, that this passage is not a parable. But how do the teachers of eternal torment know that? What proof have they offered that this passage is not a parable? Well, we are told that Jesus never used proper names in parables, and thus because this passage uses the proper name “Lazarus”, therefore it is not a parable.

But I can’t help but feel that this type of reasoning could only be believed by those who advance it to defend their position. Their logic simply begs the question. For if this passage IS a parable, then it is not true that Jesus never used proper names in parables. It also never seems to have occurred to the believers in eternal torment that Jesus may have had a very good reason to use the name “Lazarus” within this particular parable.

But beyond this, there is solid evidence that the passage is indeed a parable. Notice: Just who was Jesus addressing when he told the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus?

Then the Pharisees, who were lovers of money, heard all these things, and they ridiculed him. And he said to them… (Luke 16:14)

I ask in all sincerity; Are we to believe that Jesus was teaching the Pharisees doctrine? Are we really to believe that this passage—which is supposedly one of the clearest teachings of Jesus on the state of the afterlife and future punishment— was given for the understanding of the Pharisees? I think not. Consider:

And when his disciples asked him what this parable meant, he said, “To you it has been given to know the secrets of the kingdom of God, but for others they are in parables, so that ‘seeing they may not see, and hearing they may not understand.’ (Luke 8:9–11)

It was to the disciples that Jesus made clear the true meaning of his teachings and he plainly told them that he spoke to others in parables for the express purpose that they would not understand him.

Jesus told the story of The Rich Man and Lazarus to the Pharisees. It was precisely that audience from whom he intended to hide the true meaning of his teaching. Are you still so sure that you want to insist on a literal reading of the passage?

But there is more. A literal interpretation of the story is wholly dependent on the doctrine of the immortality of the soul — a concept that is entirely foreign to the Old Testament and is found in the New Testament only by reading our own preconceived notions into the text. If it can be shown conclusively that the scriptures speak nothing of an “immortal soul” then it immediately follows that a literal interpretation of Luke 16:19-31 is impossible. To insist that this passage is proof enough that Jesus taught the soul’s continued existence after death is once again simply begging the question.

It seems to me that in their zeal to find a “proof-text”, the believers in eternal torment have missed the entire point of the story; a point which is given in its concluding verse:

Jesus told the story of The Rich Man and Lazarus to the Pharisees. It was precisely that audience from whom he intended to hide the true meaning of his teaching. Are you still so sure that you want to insist on a literal reading of the passage?

But there is more. A literal interpretation of the story is wholly dependent on the doctrine of the immortality of the soul — a concept that is entirely foreign to the Old Testament and is found in the New Testament only by reading our own preconceived notions into the text. If it can be shown conclusively that the scriptures speak nothing of an “immortal soul” then it immediately follows that a literal interpretation of Luke 16:19-31 is impossible. To insist that this passage is proof enough that Jesus taught the soul’s continued existence after death is once again simply begging the question.

It seems to me that in their zeal to find a “proof-text”, the believers in eternal torment have missed the entire point of the story; a point which is given in its concluding verse:

He said to him, ‘If they do not hear Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead.’ ” (Luke 16:31)

In the story, the Rich Man wished to send Lazarus from the dead to warn his five brothers lest they also end up in torment. Are those five brothers literally the ones who Jesus was speaking of in his conclusion? Were they literally the ones who would not hear Moses and the prophets? Was Lazarus literally the one who they wouldn’t hear even if he rose from the dead? Should questions like these even be necessary?

No, it was the Pharisees and unbelieving Jews who would not heed Moses and the Prophets. It was Jesus who they wouldn’t believe even though he rose from the dead. THAT is the obvious point of the entire story, and to grasp even this much is to go a long way towards understanding the entire parable.

But there is a much deeper and profound meaning here which is unfortunately missed even by those who reject that the passage has anything to do with the doctrine of eternal torment. While some see only a proof-text for “hell”, those who reject that view have also often offered incredibly convoluted and unsatisfactory interpretations in an attempt to “explain away” the passage. I believe we can do better.

Before considering the details, I offer the following very brief overview of what I believe to be the true interpretation of the story:

The story presents us with a great reversal in the affairs of mankind which was about to take place. The Jews (represented by the Rich Man) who alone had been the beneficiaries of God’s revelation and had experienced the protection and blessings associated with being God’s chosen people were about to come under great judgment due to their unbelief and hardness of heart. On the other hand, the gentile nations (represented by Lazarus) were to obtain the favor of God and would be the primary beneficiaries of the gospel. The unbelieving Jewish nation would experience the torment of losing God’s favor in the current age, while the gentile nations would experience the riches of the gospel and the favor of God from which they had been previously excluded.

I feel that this interpretation is sound and obvious once we consider the entire context of the passage, as well as its context within the whole corpus of scripture. With that we offer the following justification for our conviction that this is the true interpretation of the passage.

No, it was the Pharisees and unbelieving Jews who would not heed Moses and the Prophets. It was Jesus who they wouldn’t believe even though he rose from the dead. THAT is the obvious point of the entire story, and to grasp even this much is to go a long way towards understanding the entire parable.

But there is a much deeper and profound meaning here which is unfortunately missed even by those who reject that the passage has anything to do with the doctrine of eternal torment. While some see only a proof-text for “hell”, those who reject that view have also often offered incredibly convoluted and unsatisfactory interpretations in an attempt to “explain away” the passage. I believe we can do better.

Before considering the details, I offer the following very brief overview of what I believe to be the true interpretation of the story:

The story presents us with a great reversal in the affairs of mankind which was about to take place. The Jews (represented by the Rich Man) who alone had been the beneficiaries of God’s revelation and had experienced the protection and blessings associated with being God’s chosen people were about to come under great judgment due to their unbelief and hardness of heart. On the other hand, the gentile nations (represented by Lazarus) were to obtain the favor of God and would be the primary beneficiaries of the gospel. The unbelieving Jewish nation would experience the torment of losing God’s favor in the current age, while the gentile nations would experience the riches of the gospel and the favor of God from which they had been previously excluded.

I feel that this interpretation is sound and obvious once we consider the entire context of the passage, as well as its context within the whole corpus of scripture. With that we offer the following justification for our conviction that this is the true interpretation of the passage.

THE RICH MAN

First, can we discern from the text that the Rich Man was used as a symbolical representation of the Jewish nation? Indeed, we can. Consider the following details which would have been immediately recognized by Jesus’ Jewish audience but are usually overlooked by the casual reader:

There was a certain rich man, which was clothed in purple and fine linen, and fared sumptuously every day: (Luke 16:19)

And he (the Rich Man) said, ‘Then I beg you, father, to send him (Lazarus) to my father’s house— for I have five brothers—so that he may warn them, lest they also come into this place of torment.’ (Luke 16:27–28)

If this story were simply a teaching on hell and the afterlife, then why did Jesus find it important to offer these specific details? Of what concern would the color of the Rich Man’s clothing be? Or why specify that he had exactly five brothers? Are these details superfluous? In my view these details are important keys to the proper interpretation the “Rich Man”.

To understand how these details point to the Jewish nation as the true identity of the Rich Man, some historical context is needed. Israel initially consisted of twelve tribes. These were:

Reuben

Simeon

Ephraim

Judah

Issachar

Zebulun

Dan

Naphtali

Gad

Asher

Manasseh

Benjamin

In approximately 930BC, on the succession of Solomon's son Rehoboam the united kingdom of Israel split into the northern kingdom of Israel consisting of ten tribes and the southern kingdom of Judah consisting of the tribes of Judah and Benjamin only. In approximately 722 BC the northern kingdom was conquered by the Assyrian Empire and its ten tribes were deported. To this day, these ten tribes are known as “the lost tribes” of Israel. In the time of Christ, it was only those tribes associated with the kingdom of JUDAH which remined. In fact, the word “Jew” itself means “one who is descended from Judah”.

So, it was to the unbelieving kingdom of Judah to whom Jesus preached, and it was to them he directed this parable. It is in the details of the story that we can confirm that JUDAH, and by extension the nation associated with him, is represented by the Rich Man.

To understand how these details point to the Jewish nation as the true identity of the Rich Man, some historical context is needed. Israel initially consisted of twelve tribes. These were:

Reuben

Simeon

Ephraim

Judah

Issachar

Zebulun

Dan

Naphtali

Gad

Asher

Manasseh

Benjamin

In approximately 930BC, on the succession of Solomon's son Rehoboam the united kingdom of Israel split into the northern kingdom of Israel consisting of ten tribes and the southern kingdom of Judah consisting of the tribes of Judah and Benjamin only. In approximately 722 BC the northern kingdom was conquered by the Assyrian Empire and its ten tribes were deported. To this day, these ten tribes are known as “the lost tribes” of Israel. In the time of Christ, it was only those tribes associated with the kingdom of JUDAH which remined. In fact, the word “Jew” itself means “one who is descended from Judah”.

So, it was to the unbelieving kingdom of Judah to whom Jesus preached, and it was to them he directed this parable. It is in the details of the story that we can confirm that JUDAH, and by extension the nation associated with him, is represented by the Rich Man.

“For I have FIVE BROTHERS”

Judah was the fourth son of Jacob and his first wife Leah. Of all the tribes, Judah was to become preeminent and it was through the line of Judah that the Messiah was to come. Hence, Jesus is known as “The Lion of the Tribe of Judah”. And it was JUDAH who had precisely five brothers through his mother Leah— Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Issachar, and Zebulon! This fact would have been known to Jesus’ Jewish audience and immediately recognized. Rather than being an unimportant detail, the “five brothers” are one of the keys to identifying the Rich Man.

“Clothed in Purple and Fine Linen”

Judah was also the tribe of royalty. Consider:

The scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor the ruler’s staff from between his feet, until tribute comes to him; and to him shall be the obedience of the peoples. (Genesis 49:10)

The kingly Davidic line sprung from Judah, as did the King of Kings, our Lord Jesus Christ. Judah is the tribe of royalty.

In the time of Jesus, purple was worn by, and was the color of royalty. It is in purple clothing that we find the Rich Man. The Rich man is from a royal line and has five brothers. There can be no question that Judah alone is accurately represented by this symbolism, and it is no mistake that it was to the kingdom of Judah alone that Jesus addressed this parable.

In the time of Jesus, purple was worn by, and was the color of royalty. It is in purple clothing that we find the Rich Man. The Rich man is from a royal line and has five brothers. There can be no question that Judah alone is accurately represented by this symbolism, and it is no mistake that it was to the kingdom of Judah alone that Jesus addressed this parable.

LAZARUS

As we pointed out earlier, the teachers of eternal torment put great emphasis on the proper name “Lazarus” and attempt to use it as proof that Jesus was relating a true history of real individuals rather than telling a colorful parable. We pointed out that this reasoning is a classic non-sequitur and an incredibly weak argument. Indeed, if the story is a parable then it is not true that Jesus never used proper names in parables. The most we would be able to discern is that Jesus only used a proper name in this particular parable. But again, it seems to have never occurred to them that there might have been a reason why Jesus used this particular name “Lazarus” for the poor beggar.

We have proposed that “Lazarus” is a representation of the Gentile nations which, although previously excluded from God’s favor and blessing were about to become the beneficiaries of the riches of the Gospel, while the Jewish nation would be cast off.

But why use the name “Lazarus” to represent the gentile nations? Again, the reason and meaning would be obvious to Jesus’ Jewish audience, but it truly remarkable that almost all Christian readers miss it in their zeal only to find a proof-text for the doctrine of eternal torment.

Just who is Lazarus?

We have proposed that “Lazarus” is a representation of the Gentile nations which, although previously excluded from God’s favor and blessing were about to become the beneficiaries of the riches of the Gospel, while the Jewish nation would be cast off.

But why use the name “Lazarus” to represent the gentile nations? Again, the reason and meaning would be obvious to Jesus’ Jewish audience, but it truly remarkable that almost all Christian readers miss it in their zeal only to find a proof-text for the doctrine of eternal torment.

Just who is Lazarus?

Strong’s 2976Λάζαρος [Lazaros/lad·zar·os/] n pr m. Probably of Hebrew origin 499; GK 3276; 15 occurrences; AV translates as “Lazarus” 11 times, and “Lazarus (the poor man)” four times. 1an inhabitant of Bethany, beloved by Christ and raised from the dead by him. 2a very poor and wretched person to whom Jesus referred to in Luke 16:20–25. Additional Information:Lazarus = “whom God helps” (a form of the Hebrew name Eleazar).

A Jew would have immediately recognized that “Lazarus” is the Greek equivalent of the Hebrew name Eleazer, and the significance would have been immediately apparent to them. Notice:

After these things the word of the Lordcame to Abram in a vision: “Fear not, Abram, I am your shield; your reward shall be very great.” But Abram said, “O Lord God, what will you give me, for I continue childless, and the heir of my house is Eliezer of Damascus?” And Abram said, “Behold, you have given me no offspring, and a member of my household will be my heir.” And behold, the word of the Lordcame to him: “This man shall not be your heir; your very own son shall be your heir.” And he brought him outside and said, “Look toward heaven, and number the stars, if you are able to number them.” Then he said to him, “So shall your offspring be.” And he believed the Lord, and he counted it to him as righteousness. (Genesis 15:1–6)

Notice how plain and profound the meaning becomes once we realize that Lazarus is Eliezer— the one who was REJECTED as the true heir of Abraham. This gentile servant, the one who God rejected as the heir was used to represent the gentile nations who the Jews, the natural children of Abraham came to view with contempt.

Even Jesus himself expressed the attitude of the Jews towards the other nations when he encountered a gentile woman pleading for his help:

Even Jesus himself expressed the attitude of the Jews towards the other nations when he encountered a gentile woman pleading for his help:

But immediately a woman whose little daughter had an unclean spirit heard of him and came and fell down at his feet. Now the woman was a Gentile, a Syrophoenician by birth. And she begged him to cast the demon out of her daughter. And he said to her, “Let the children be fed first, for it is not right to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs.” But she answered him, “Yes, Lord; yet even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs.” And he said to her, “For this statement you may go your way; the demon has left your daughter.” (Mark 7:25–29)

Compare these words with the description of Lazarus given in Luke 16:

(Lazarus) desired to be fed with what fell from the rich man’s table. Moreover, even the dogs came and licked his sores. (Luke 16:21)

There really is no mystery as to the true identification of either the Rich Man or of Lazarus. The Rich Man is clearly a symbolical representation of Judah, or the unbelieving Jewish Nation, while Lazarus represents the gentile nations. No, the true mystery is why so many Christians insist on wooden literalism that blinds them to these obvious and profound truths.

LAW, DIVORCE, REMARRIAGE, AND DEATH

Luke chapter 16 contains an odd structure which on first glance seems rather random. Notice:

Verses 1-13 The Parable of the Dishonest Manager

Verses 14-17 Teaching about the Law

Verse 18 Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage

Verses 19-31 The Rich Man and Lazarus

Why do two seemingly out of place topics, the teaching about the law, and the teaching concerning divorce and remarriage, appear in between these two parables, and as a prelude to the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus?

Have those who seek to find here a proof-text for “hell” ever taken the time to consider this question, much less explain it? Are we to believe that Jesus’ discourse was so disjointed—that he spoke of the law, then divorce, and then hell — three seemingly unrelated topics all within the space of 17 verses, without any reason or connection between them?

This is no trivial matter, and I shall attempt to show that Jesus’ teaching about the law (vs. 14-17), and divorce and remarriage (vs. 18) are crucial to the proper interpretation of his story of the Rich Man and Lazarus.

In verses 15-16 Jesus speaks about the law and rebukes the Pharisees:

Verses 1-13 The Parable of the Dishonest Manager

Verses 14-17 Teaching about the Law

Verse 18 Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage

Verses 19-31 The Rich Man and Lazarus

Why do two seemingly out of place topics, the teaching about the law, and the teaching concerning divorce and remarriage, appear in between these two parables, and as a prelude to the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus?

Have those who seek to find here a proof-text for “hell” ever taken the time to consider this question, much less explain it? Are we to believe that Jesus’ discourse was so disjointed—that he spoke of the law, then divorce, and then hell — three seemingly unrelated topics all within the space of 17 verses, without any reason or connection between them?

This is no trivial matter, and I shall attempt to show that Jesus’ teaching about the law (vs. 14-17), and divorce and remarriage (vs. 18) are crucial to the proper interpretation of his story of the Rich Man and Lazarus.

In verses 15-16 Jesus speaks about the law and rebukes the Pharisees:

And he said to them, “You are those who justify yourselves before men, but God knows your hearts. For what is exalted among men is an abomination in the sight of God. “The Law and the Prophets were until John; since then the good news of the kingdom of God is preached, and everyone forces his way into it. (Luke 16:15–16)

As we have previously stated, the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus was given to explain that a great reversal in the fortunes of the both the Jewish and gentile nations was about to take place. Jesus alludes to this when he tells the Pharisees that “The law and the prophets were until John (the Baptist) but since then the good news of the kingdom of God is preached.” This is a reference to the old and new covenants; the former under the law of Moses, and the new covenant of the gospel. From the time John the Baptist began to preach: “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand” (Matt 3:2), the time of the new covenant (in which the gospel would be preached to the gentiles) had come, and the old covenant (in which God had dealt exclusively with the Jews) was passing away. The story of Lazarus and the Rich man is the story of how this changing of the covenant from the old to the new would affect both the Jews and the gentiles. But then notice something peculiar:

“The law and the prophets were until John” (vs. 16)

But it is easier for heaven and earth to pass away than for one dot of the Law to become void. (vs. 17)

This is peculiar because it might at first appear to create a contradiction. The law and the prophets were UNTIL John, but yet not one dot of the law was to become void. I remember as a young Christian being both confused and concerned about passages like these. As Christians we are taught to believe that we are not under and have been freed from the law. And yet Jesus instructs us that not one dot of the law shall become void (see also Matt 5:18).

Of course, I soon came to learn that there is in fact no contradiction here at all. The Bible makes clear exactly how both things are true; how Christians are free from the law, and yet not one particle of the law shall become void. We will return to this point shortly.

But notice that immediately after this, in verse 18, that Jesus launches into what at first appears to be a completely out of place and unrelated teaching on divorce and remarriage. Jesus gives this teaching as the immediate preludeto the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus. Jesus’ teaching on the law and the prophets makes perfect sense within the context of the story. But why this? Why here? The teaching on divorce and remarriage seems straightforward enough in itself, but what could possibly explain the unusual context?

I submit that the reason is because this teaching on divorce and remarriage is the key to understanding one of the primary aspects of both the Rich man and of Lazarus; namely, that they both had to die in order for their great reversal in fortune to take place.

How so? I return to the apparent contradiction I mentioned above; that believers under the new covenant are not under the law, and yet not one particle of the law will be made void. How does the Bible reconcile this difficulty?

The Bible is clear: the believer must die to the law.

This is no mere expression of language. By virtue of the believer’s position in Christ, Christians are reckoned as connected with him concerning both his death and his resurrection. Hence Christians are dead to the law in Christ that they may be the recipients of the new covenant.

Paul takes up this very topic in Romans chapter 7. In verse 1 he gives the problem:

Of course, I soon came to learn that there is in fact no contradiction here at all. The Bible makes clear exactly how both things are true; how Christians are free from the law, and yet not one particle of the law shall become void. We will return to this point shortly.

But notice that immediately after this, in verse 18, that Jesus launches into what at first appears to be a completely out of place and unrelated teaching on divorce and remarriage. Jesus gives this teaching as the immediate preludeto the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus. Jesus’ teaching on the law and the prophets makes perfect sense within the context of the story. But why this? Why here? The teaching on divorce and remarriage seems straightforward enough in itself, but what could possibly explain the unusual context?

I submit that the reason is because this teaching on divorce and remarriage is the key to understanding one of the primary aspects of both the Rich man and of Lazarus; namely, that they both had to die in order for their great reversal in fortune to take place.

How so? I return to the apparent contradiction I mentioned above; that believers under the new covenant are not under the law, and yet not one particle of the law will be made void. How does the Bible reconcile this difficulty?

The Bible is clear: the believer must die to the law.

This is no mere expression of language. By virtue of the believer’s position in Christ, Christians are reckoned as connected with him concerning both his death and his resurrection. Hence Christians are dead to the law in Christ that they may be the recipients of the new covenant.

Paul takes up this very topic in Romans chapter 7. In verse 1 he gives the problem:

Or do you not know, brothers—for I am speaking to those who know the law--that the law is binding on a person as long as he lives? (Romans 7:1)

Then in verses 4-6 he gives the solution:

Likewise, my brothers, you also have died to the law through the body of Christ, so that you may belong to another, to him who has been raised from the dead, in order that we may bear fruit for God. For while we were livingin the flesh, our sinful passions, aroused by the law, were at work in our members to bear fruit for death. But now we are released from the law, having diedto that which held us captive, so that we serve in the new way of the Spirit and not in the old wayof the written code. (Romans 7:4–6)

This is majestically profound teaching. God’s law is perfect. God’s law stands. God’s law cannot and will not pass away. The only way for a believer to be freed from the law is to die. By putting our faith in Christ we are dead to the law along with him.

But right between the stating of the problem and this remarkably profound answer, Paul gives us an illustration which not only explains how believers can be free from the law by dying to it, but one which also completely explains the entire strange context of the Rich Man and Lazarus— a context that fist appears disjointed and misplaced but is now shown to be crucial. Paul explains:

But right between the stating of the problem and this remarkably profound answer, Paul gives us an illustration which not only explains how believers can be free from the law by dying to it, but one which also completely explains the entire strange context of the Rich Man and Lazarus— a context that fist appears disjointed and misplaced but is now shown to be crucial. Paul explains:

For a married woman is bound by law to her husband while he lives, but if her husband dies she is released from the law of marriage. Accordingly, she will be called an adulteress if she lives with another man while her husband is alive. But if her husband dies, she is free from that law, and if she marries another man she is not an adulteress. (Romans 7:2–3)

Consider again the context of the Rich Man and Lazarus, and then notice how Paul has connected the concepts of the law, divorce and remarriage, and death in precisely the same way.

Luke 16 Verses 14-17 Teaching about the Law

Luke 16 Verse 18 Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage

Luke 16 Verses 19-31 The Rich Man and Lazarus both Die

The old covenant was about to pass away, but the law would not and could not pass away. The Jewish nation had forsaken the old covenant. Notice how this is described in Malachi chapter 2:

Luke 16 Verses 14-17 Teaching about the Law

Luke 16 Verse 18 Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage

Luke 16 Verses 19-31 The Rich Man and Lazarus both Die

The old covenant was about to pass away, but the law would not and could not pass away. The Jewish nation had forsaken the old covenant. Notice how this is described in Malachi chapter 2:

Why then are we faithless to one another, profaning the covenant of our fathers? Judah has been faithless, and abomination has been committed in Israel and in Jerusalem. For Judah has profaned the sanctuary of the Lord, which he loves, and has married the daughter of a foreign god.(Malachi 2:10–11)

Do you see it? By forsaking God’s covenant, Judah (the Rich Man) had married “the daughter of a foreign god”. They had put away the law covenant which God had given them. But the law could not pass away thus leaving it as a living spouse! Anyone who therefore tried to be married to the law would thus be an adulterer!

Does this not completely explain Jesus’ teaching on divorce and remarriage directly in between his teaching about the law, and the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus?

The change from the old to the new covenant which would reverse the fortunes of both the Jews and the gentiles could only come about in one way: Both parties which stood in relation to the law, a law which could not pass away, had to die. The gentile nations could never be justified by the law, and any attempt to do so would be nothing less than spiritually adultery. However, by their union with the death and resurrection of Christ they were freed from the law that they might be married to him in the new covenant. Therefore, as Paul states:

Does this not completely explain Jesus’ teaching on divorce and remarriage directly in between his teaching about the law, and the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus?

The change from the old to the new covenant which would reverse the fortunes of both the Jews and the gentiles could only come about in one way: Both parties which stood in relation to the law, a law which could not pass away, had to die. The gentile nations could never be justified by the law, and any attempt to do so would be nothing less than spiritually adultery. However, by their union with the death and resurrection of Christ they were freed from the law that they might be married to him in the new covenant. Therefore, as Paul states:

If you are Christ’s, then you are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to promise. (Galatians 3:29)

Lazarus (Eliezer) who represented the gentile nations had now become Abraham’s heir and was taken to his bosom (Luke 16:22). Whereas God had once told Abraham, “He (Eliezer, Lazarus) shall not be your heir”, the termination of the old covenant resulted in him obtaining the favor and wealth of the gospel— something that was not possible unless he died.

But what about the Rich Man who represented the wicked and unbelieving Jewish nation (Judah)? The termination of the old covenant would result in a much different kind of death for him; one of torment under the fiery judgment of God. Jesus had warned the Jews:

But what about the Rich Man who represented the wicked and unbelieving Jewish nation (Judah)? The termination of the old covenant would result in a much different kind of death for him; one of torment under the fiery judgment of God. Jesus had warned the Jews:

Therefore I tell you, the kingdom of God will be taken away from you and given to a people producing its fruits. (Matthew 21:43)

In 70 AD the Roman armies sacked the city of Jerusalem destroying the Jewish nation, the temple, and all of the trappings of the old covenant including the system of animal sacrifice which had stood for thousands of years. The Jewish people were exiled from their ancestral land and were dispersed among the gentile nations for nearly twenty centuries. No one who is familiar with Jewish history can have any doubt about the torment and persecution endured by Jewish people.

The reversal of fortunes was complete. Lazarus (the gentiles) had now obtained comfort and mercy (the riches and blessing of the New Covenant) while The Rich Man (the Jewish nation) was tormented under the fiery judgment of God (destruction, exile, persecution, exclusion). Lazarus (the gentiles) was dead in Christ by which he obtained blessing, while the Rich Man (the Jewish nation) suffered national death by which they were tormented.

The reversal of fortunes was complete. Lazarus (the gentiles) had now obtained comfort and mercy (the riches and blessing of the New Covenant) while The Rich Man (the Jewish nation) was tormented under the fiery judgment of God (destruction, exile, persecution, exclusion). Lazarus (the gentiles) was dead in Christ by which he obtained blessing, while the Rich Man (the Jewish nation) suffered national death by which they were tormented.

A GREAT CHASM FIXED

And besides all this, between us and you a great chasm has been fixed, in order that those who would pass from here to you may not be able, and none may cross from there to us.’ (Luke 16:26)

Believers in eternal torment point to this verse in an attempt to prove that that the conditions of both the Rich Man and Lazarus were fixed and unchangeable following their deaths. But this is an error for several reasons.

First, the passage says nothing concerning the actual duration of the fates of either the Rich Man or Lazarus.

Second, as I pointed out at the beginning of this essay, any interpretation which would make a condition in hades eternal is simply impossible. Hades must give up all the dead prior to the final judgment. Therefore, this passage speaks nothing of any condition which follows the judgment, much less of a permanent and unchangeable condition for either party.

But the passage does speak of a great gulf, or chasm, fixed between the Rich Man and Lazarus so that neither party can pass to the other side. Given our interpretation that the story was told in order to relay the soon to come reversal of fortunes for both Jew and gentile, the true meaning is not hard to find.

In fact, the answer as well as the real, final, and permanent outcome of both parties can be found in one of the longest and most detailed theological treatises in all of scripture—Romans chapters 9-11.

Here Paul addresses this “great chasm” and takes up the difficult question of why it appeared that God had cast away his chosen people, the Jews. He explains why only a small remnant of them had come to faith in Christ and had believed the gospel. Paul says:

First, the passage says nothing concerning the actual duration of the fates of either the Rich Man or Lazarus.

Second, as I pointed out at the beginning of this essay, any interpretation which would make a condition in hades eternal is simply impossible. Hades must give up all the dead prior to the final judgment. Therefore, this passage speaks nothing of any condition which follows the judgment, much less of a permanent and unchangeable condition for either party.

But the passage does speak of a great gulf, or chasm, fixed between the Rich Man and Lazarus so that neither party can pass to the other side. Given our interpretation that the story was told in order to relay the soon to come reversal of fortunes for both Jew and gentile, the true meaning is not hard to find.

In fact, the answer as well as the real, final, and permanent outcome of both parties can be found in one of the longest and most detailed theological treatises in all of scripture—Romans chapters 9-11.

Here Paul addresses this “great chasm” and takes up the difficult question of why it appeared that God had cast away his chosen people, the Jews. He explains why only a small remnant of them had come to faith in Christ and had believed the gospel. Paul says:

What shall we say, then? That Gentiles who did not pursue righteousness have attained it, that is, a righteousness that is by faith; but that Israel who pursued a law that would lead to righteousness did not succeed in reaching that law. (Romans 9:30–31)

Because of the Jew’s unbelief, Paul asks:

I ask, then, has God rejected his people? (Romans 11:1a)

Given our interpretation of the Rich Man and Lazarus we might ask a similar and parallel question: Is the Rich Man then lost forever? Our brethren who believe in eternal torment say yes. What does Paul say?

By no means! (Romans 11:1b)

Paul then goes on to say that first, there was even then a remnant of the Jewish people who had believed the gospel. God had not fully cast off his people. But the difficult question still remained; Why had the nation collectively rejected their own Messiah and continued in unbelief? The answer is both surprising and troubling unless we are willing to hear Paul’s case through to the end:

What then? Israel failed to obtain what it was seeking. The elect obtained it, but the rest were hardened, as it is written, “God gave them a spirit of stupor, eyes that would not see and ears that would not hear, down to this very day.” (Romans 11:7–8)

The unbelief of the Jewish nation was the work of God himself. It was God who fixed this great chasm of unbelief between the unbelieving Jews and the believing gentiles. But was this to be a permanent condition? Were the Jews to remain in unbelief forever? No. Paul answers to both the reason and the duration of their condition.

First the reason:

First the reason:

So I ask, did they stumble in order that they might fall? By no means! Rather, through their trespass salvation has come to the Gentiles, so as to make Israel jealous. (Romans 11:11)

God did not blind the Jewish people simply to punish them. No, their blindness has a greater two-fold purpose. First, that the gospel would be preached to, and believed by the gentiles. Second, to provoke the Jewish people to jealousy by excluding them from the riches of the Gospel.

Next, the duration of their condition:

Next, the duration of their condition:

For I would not, brethren, that ye should be ignorant of this mystery, lest ye should be wise in your own conceits; that blindness in part is happened to Israel, untilthe fulness of the Gentiles be come in. And so all Israel shall be saved: as it is written, There shall come out of Sion the Deliverer, and shall turn away ungodliness from Jacob: For this is my covenant unto them, when I shall take away their sins. As concerning the gospel, they are enemies for your sakes: but as touching the election, they are beloved for the fathers’ sakes. For the gifts and calling of God are without repentance. For as ye in times past have not believed God, yet have now obtained mercy through their unbelief: Even so have these also now not believed, that through your mercy they also may obtain mercy. For God hath concluded them all in unbelief, that he might have mercy upon all. O the depth of the riches both of the wisdom and knowledge of God! how unsearchable are his judgments, and his ways past finding out! (Romans 11:25–33)

It is only here that we find what is, in the end, to become of the Rich Man (the unbelieving Jews). They are to remain blinded until Jesus returns and converts them. They previously had obtained mercy at the expense of the gentile nations. For now, this situation has been reversed. In this age the gentiles have received mercy while the Jewish nation has experienced harness of heart, unbelief, persecution, and torment. God in his infinite plan has concluded all in unbelief—first the gentiles, and now the Jewish people, but only so that in the end He may have mercy upon ALL. The Rich Man of our story is not lost forever, and to that we can only say with the apostle Paul:

“O the depth of the riches both of the wisdom and knowledge of God! how unsearchable are his judgments, and his ways past finding out!”.

SUMMARY

So in summary what we have learned?

- The story of the Rich Man and Lazarus cannot be relating an eternal condition because the place to which both were consigned is represented by the Greek word hades which must be emptied before the final judgment of mankind.

- An argument in favor of a literal interpretation of the passage fails because it relies on the flimsy assumption that Jesus never used proper names in parables. This argument is not only a classic non-sequitur, but fails to account for any reason for which Jesus may have used the proper name “Lazarus” in this particular parable.

- An argument for the literal interpretation of the passage fails because it was specifically addressed to the Pharisees, an audience about which Jesus made clear that he spoke to them in parables for the express purpose that they would not understand his teaching.

- The conclusion of the parable – “If they hear not Moses and the prophets, etc.” is strong evidence that the passage is not literal but instead deals with the unbelieving Jews to whom it was addressed—those who neither heeded the scriptures, nor would hear Jesus, even though he rose from the dead.

- The Rich Man is easily identified as the remaining kingdom of Judah in three ways. First, that they alone had experienced the richness of the oracles and favor of God to the exclusion of all other nations. Second, that the Rich Man is identified as having five brothers as also Judah did through his mother Leah. Third, that the Rich Man is clothed in the color of royalty signifying the royal line of kings which came through Judah - the kingship ultimately passing to our Lord who is “The Lion of the Tribe of Judah.”

- Lazarus is easily identified as the gentile nations in at least two ways. First, that the name Lazarus is merely a form of the name Eliezer, the gentile servant in the household of Abraham who was rejected by God as the true heir. Second, because it was the gentiles who are represented in another place as those longing for the crumbs which fall from their master’s table in just the same language in which Lazarus is described.

- The parable thus represents a great change in fortune which was about to befall both the Jews and the Gentiles. One in which the Jews would fall from God’s favor and experience torment, while the gentiles would gain the favor of God in Christ, gladly receive the gospel, and prove by doing so that they were true heirs of Abraham.

- That the deaths of both the Rich Man and Lazarus are explained by Jesus’ seemingly misplaced teaching on both the Law, and divorce and remarriage, which immediately precedes this parable.

- The Law and prophets were until the preaching of John the Baptist. Since that time the gospel of the kingdom was preached.

- Even though there was to be a change in God’s covenant relationship with mankind, not one particle of the law could be made void.

- The law was given to the Jewish people in a relationship likened to that of a loving spouse. The Jews however defiled this relationship and “married the daughter of a foreign god” thus divorcing the law covenant.

- This produced a situation where the Jews had broken and divorced the law covenant, but the Gentiles could never be joined to it. As a living but divorced spouse any who sought to be justified by the law covenant would commit spiritual adultery.

- Thus, only those who have died to the law by their faith in, and union with Christ are free to be justified by the new covenant.

- The same concepts of law, death, divorce, remarriage, and spiritual adultery given by Jesus in Luke 16 are exactly those same metaphors employed by the apostle Paul in his teaching on how those in Christ are made free from the law.

- This relationship explains the deaths of both Rich man and Lazarus within the parable. As the Old Covenant passed away any who stood in relation to the law had to undergo a death to the law. And so, both the Rich Man (the Jewish Nation), and Lazarus (the gentile nations), died.

- The gentile nations through union with Christ would die with him in regard to the law. The Jewish nation, on the other hand, would experience a national death.

- This death resulted in a reversal of fortunes for both the Jewish nation and the gentile nations so that, whereas the Jews had previously benefited from God’s exclusive favor they would now be tormented under his judgment, while the gentiles by the gospel would become objects of God’s mercy and affection.

- The torment of the Rich man was fulfilled in the destruction of the Jewish nation, the destruction of the temple and sacrificial system, and their exile and persecution among the nations for nearly twenty centuries.

- A “great” chasm of time and unbelief was fixed between the believing gentiles and the unbelieving Jews.

- This chasm of unbelief was the work of God himself who blinded the eyes and hardened the hearts of the Jews.

- The plight and torment of the Rich man which signified the unbelieving Jewish nation is not a permanent or endless condition. Their time of unbelief and torment will end at the return of Christ when he removes their blindness and saves “all Israel”.

- Thus, any interpretation which seeks to find in the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus a wooden literalism only in order to prop up the doctrine of eternal torment completely fails to comprehend the true meaning of the story, and fails to explain numerous details as well as the entire context of the passage.